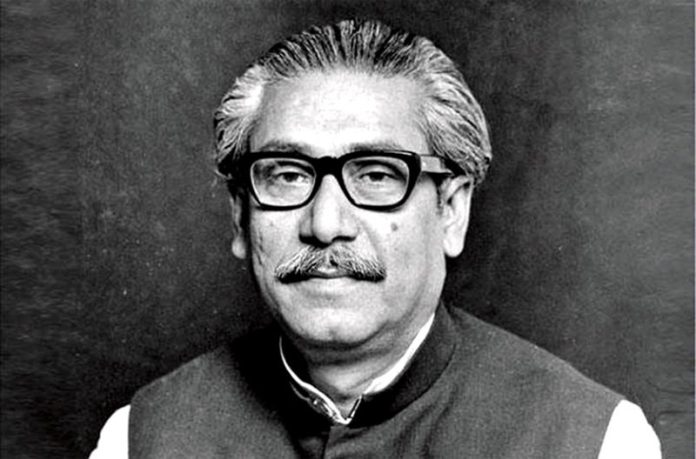

A Pakistan army commando squad arrested Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman from his 32 Dhanmondi residence as they simultaneously launched crackdown on the March 25, 1971 black night initially exposing the nation to a state of wilderness about his whereabouts.

The commander of the squad, an officer of Pakistan military’s Special Service Group (SSG), years later described operational details of his ‘mission’.

But world famous New York Times (NYT) archive now reveals that Bangabandhu himself gave a vivid description to the newspaper’s world renowned reporter Pulitzer Prize winning Sydney Hillel Schanberg along with a few other American journalists about the episode.

The NYT carried a report on the description with a headline — “He Tells Full Story of Arrest and Detention – as Bangladesh’s Father of the Nation gave the interview just a week after his return home after nine months of captivity in Pakistan.

“They may kill me. I may never see you again. But my people will be free some day and my soul will see it and be happy,” The NYT quoted Bangabandhu as telling his weeping wife Begum Fazilatunnesa Mujib.

His two sons minor Sheikh Russell and Sheikh Jamal were there as he bade goodbye and “kissed each member of the family”.

But hours ahead of that moment, according to the NYT, Bangabandhu had made some secret preparations with reports mounting that an army crackdown was imminent against the popularly elected movement seeking to end the long West Pakistani domination and exploitation of the more populous eastern region.

“At 10:30 P.M. he called a clandestine headquarters in Chittagong (now Chottagram), the southeastern port city, and dictated a last message to his people, which was recorded and later broadcast by secret transmitter,” the NYT report read.

According to the NYT, the gist of the broadcast was that they should resist any army attack and fight on “regardless of what might happen to their leader” and “he also spoke of independence for the 75 million people of East Pakistan”.

Bangabandhu told the US journalists that after sending his message he ordered to go away the men of the paramilitary East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) and of the Awami League, who were guarding him.

“The West Pakistani attack throughout the city began at about 11 P.M. and quickly mounted in intensity. The troops began firing into Sheikh Mujib’s house between mid night and 1 A.M.,” read the report which the NYT carried on the front page of its January 18, 1972 edition.

It said Bangabandhu had recalled that as the bullets whizzed over head, he pushed his wife and the two children into his dressing room upstairs and they all got clown on the floor.

“That (interview) was a piece of his narrative today as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman related for the first time the full story of his arrest and imprisonment and narrow escapes from death-and his release a week ago,” Schanberg wrote.

The famous US journalist wrote “relaxed and with little bitterness, and sometimes laughing at his good fortune, the Prime Minister of the newly proclaimed nation of Bangladesh talked in fluent English with a handful of American newspaper correspondents”.

According to the NYT Bangabandhu talked to the US journalists leaning back on a couch “in the sitting room of the occasional official residence of his captor, former President Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan of Pakistan, who is himself now under house arrest in West Pakistan, and started from the beginning-the night of March 25”.

The NYT report said after Bangabandhu said goodbye to his family, the West Pakistani soldiers prodded him down the stairs and as he reached their jeep, “in a reflex of habit and defiance, (Bangabandhu) said: ‘I have forgotten my pipe and tobacco. I must have my pipe and tobacco!'”.

“The soldiers were taken aback, puzzled, but they escorted him back into the house, where his wife handed him the pipe and the tobacco pouch,” the report read.

Bangabandhu, it said, was then “driven off to nine and a half months of imprisonment by the Pakistani Government for his leadership of the Bengali autonomy movement here in East Pakistan”.

Bangabandhu said he had learned of a plot by the Pakistani military regime to kill him and lay it to the Bengalis.

“Whenever I came out of the house,” he related “they were going to throw a grenade at my car and then say Bengali extremists did it and that was why the army had to move in and take action against my people.

“I decided I must stay in my own house and let them kill me in my own house, so that everybody would know they had killed me, and my blood would purify my people,” the NYT quoted Bangabandhu as saying.

But, Bangabandhu recalled he had sent his eldest son, Kamal, and his two daughters into hiding but “unknown to them (Bangabandhu couple), their middle son, Jamal, was still in the house, sleeping in his room” at the “modest two-story house in the Dhanmondi section of Dacca”.

“By 10 P.M. Sheikh Mujib had received word that West Pakistani troops had taken up positions to attack the civilian population. A few minutes later troops surrounded his house and a mortar shell exploded nearby.”

The NYT wrote the troops soon broke into the house, killing a watchman who had refused to leave, and stormed up the stairs and “Sheikh Mujib said he opened the door of the dressing room and faced them.

“Stop shooting! Stop shooting! Why are you shooting? If you want to shoot me, then shoot me; here I am, but why are you shooting my people and my children?,” Bangabandhu told the US journalists.

He recalled after another flurry a major halted the men and told then there would be no more shooting and “told Sheikh Mujib he was being arrested and, at his request, allowed him a few moments to say his farewells”.

The Pakistani documents, meanwhile, suggested after Bangabandhu’s arrest the military headquarters in Dhaka was sent a radio message saying, the “Big bird (is now) in the cage”.

Bangabandhu said after he got onboard the military jeep he was initially driven to the National Assembly building, “where I was given a chair.”

“Then they offered me tea,” he recalled in a voice that became mocking. “I said, ‘That’s wonderful. Wonderful situation. This ‘is the best time of my life to have tea,'” Bangabandhu recalled.

After a while he was taken to “a dark and dirty room” at a school in the military cantonment and for the next six days he spent his days in that room and his nights-midnight to 6 A.M.- in a room in the residence of the martial-law administrator Lieutenant General Tikka Khan.

The NYT wrote that man the Bengalis considered most responsible for the military repression, in which hundreds of thousands of Bengalis were tortured and killed.

“On April 1, Sheik Mujib said, he was flown to Rawalpindi, in West Pakistan-separated from East Pakistan by over a thousand miles of Indian territory-and then moved to Mianwali Prison and put in the condemned cell,” the report read.

The NYT added Bangabandhu passed the next nine months alternating between that prison and two others, at Lyallpur and at Sahiwal, all in the northern part of Punjab Province.

“The military Government began proceedings against him on 12 charges, six of which carried the death penalty. One was ‘waging war against Pakistan’,” it said.

Pakistan military’s SSG colonel ZA Khan, who led the squad in 32 Dhanmondi, later in an interview said he was posted in Cumilla and came to Dhaka on March 23 when he was assigned to carryout the task.

According to Khan, who was known for his arrogance and snobbery in close military circle at that time, major general Rao Farmman Ali gave him the formal order to arrest Bangabandhu.

Khan said Ali, who was tasked to oversee the civilian affairs, first asked him to accomplish the task without using military troops and taking with him only one officer in a civilian car.

According to Khan he declined to accept the order considering it to be an impossible idea because of the constant vigilant crowds at 32 Dhanmondi, which infuriated Ali.

Eventually Pakistan’s army chief General Abdul Hamid, who was in Dhaka at that time interfered and allowed the use of commandos in full battle gears.

“The COAS (Hamid) then telephoned Major General Rao Farman and told him to meet all my requirements and told me that Mujib was to be taken alive and that I would be personally responsible if he was killed,” Khan said.

The officer explained in details the obstacles set to prevent military vehicle movement towards Bangabandhu residence and how his men eventually reached the scene to arrest him at the designated “H Hour”.

Khan said reaching near the house fire was opened, some people in the compound ran out of the gate and the perimeter around the house was formed.

He said the police guard outside the house got into their 180 pounder tent, lifted the tent by its poles and ran into the lake in front of the house.

“It was pitch dark, the house search party entered the house,” Khan said adding a civilian guard at the house tried to attack one of his soldiers with a “dah”, a long bladed knife.

He said the man was shot by a soldier from behind “but did not kill him”.

Khan’s men found none on the ground floor and on the first floor “one room was locked and sound could be heard that indicated people were in

the room”.

“I told Major Bilal to have the door broken down and went downstairs to check if Captain Saeed had arrived and if any crowd had formed,” he recalled.

Khan said while he was instructing Captain Saeed, there was a sound of a shot, then grenade exploded and was followed by a burst of sub-machine gun.

“I was certain that Mujib had been killed,” Khan said adding he ran upstairs and was relieved to see him alive and unhurt.

“I asked him to accompany me and he asked to be allowed to say good bye to his family which I allowed,” Khan claimed.

Khan said he later learnt that from the veranda of one of the rooms a shot had been fired towards the soldiers and in retaliation they threw a grenade and fired a burst from a SMG.

“After the firing Sheikh Mujib . . . came out and was arrested,” Khan said. -BSS