The football genius Diego Maradona celebrates his 60th birthday on Friday, a day many of us doubted this most complex of men would ever see.

His has been a life that has hit the very highest of peaks before descending into the deepest, darkest troughs of despair, unable to cope with the adulation that came with stardom and the god-like status bestowed upon him, yet seemingly incapable of surviving without it, reports BBC.

To understand Diego properly you have to know the enigma that is Argentina; a country that needs the Diegos of this world to be the Messiahs that can carry it to the level of greatness of which it considers itself worthy. And to appreciate that this is a man who has lived a story replete with incredible paradoxes, a host of mistakes and subsequent corrections, epic feats and anecdotes about declines and resurrections.

Which one is the real Maradona?

Diego the boy from the Buenos Aires shanty town of Villa Fiorito, a prodigiously talented street urchin and man of the people?

Or maybe Maradona the god, the myth, the great avenger and the embodiment of the people’s dreams, aspirations and ultimate confirmation that Argentina is the best country in the world? Maybe both are.

In 1968 Francis Cornejo, the coach of a youth side affiliated to Argentinos Juniors that he called Cebollitas (little onions) had to travel to Villa Fiorito to check the kid’s age on his ID. “He’s tiny, there’s no way he’s eight,” was his stunned reaction as he watched him play in a trial.

His mother Dalma Salvadora Franco confirmed his age by showing them Diego’s birth certificate from Evita Hospital. Francis had just performed the footballing equivalent of striking oil. He had found a gem that could slot into his side. From March 1969 onwards, the team did not tire of winning, recording a 136-game unbeaten run.

In his youth, Maradona’s dad, or as his friends called him Chitoro, piloted a ferry that moved cattle from village to village and later on he went on to work in a chemical factory, where he barely earned enough to make ends meet for his large family in the shanty town where they lived.

The success of his son, the fifth of eight children, meant that apart from becoming the “king of the barbecue”, he would never work again. By the time Diego was 15 he had already become the head of the family and told his dad to be by his side.

From an early age Diego learned that leadership was a natural step forward, particularly when there was a vacuum to fill, no matter what your age. “We went to play in Brazil,” recalls team-mate Ruben Favret who, like the rest of the squad, played midweek friendlies in Argentina and abroad to take advantage of Maradona’s pull.

“It was the era of the colour television and we all wanted to bring one back. But we had not been paid our bonuses. Diego, who was 18, stood up for everyone and told Consoli [the president of Argentinos] that if they didn’t pay us, he wouldn’t play.”

A complicated, convoluted move to Boca Juniors followed, mostly orchestrated by Maradona himself who revealed – incorrectly – to a friendly journalist that talks to sign him from Argentinos were at an advanced stage.

It kick-started the first great media-led transfer in history, for what was then a still fairly green 20-year-old. The deal morphed into the surreal. What began as a straight purchase for the not inconsiderable sum of $10m became a last-minute loan using six Boca players, some cash and dodgy cheques as collateral. Nothing was simple or straightforward when it concerned Maradona.

Barcelona, where he went next, never saw the best of him. Of the two years he spent there he was out ill or injured for about half of that. He suffered an appalling ankle injury after a dreadful tackle from Athletic Club’s Andoni Goicoechea and then, when he became the main protagonist in a massive brawl played out in front of the Spanish king in the Copa del Rey final which led to a five-month ban from domestic competition, his fate was all but sealed.

In fact, he was close to bankruptcy at that point and a move, with new financial incentives, was a necessity. Also, he never adapted to life in Catalonia, where he was made to feel an outsider.

Two months later he signed for Napoli, where he would enjoy his most successful and ultimately most punishing times. The move to this noisy, crowded, overheated goldfish bowl of an existence – in which the Neapolitan criminal organisation, the ever-present Camorra, were involved from the start – was the moment Diego the kid from Fiorito became Maradona the brand.

Suddenly he was more the character than the kid, falling in love with the notion of being Maradona, lapping up the glory and adulation yet always fully aware of just how asphyxiating the whole situation was.

Cocaine became his new reality, a place of excitement higher than he had ever been before; his drug of choice removed him from the demanding realities of having to constantly demonstrate that you are the best player in the world.

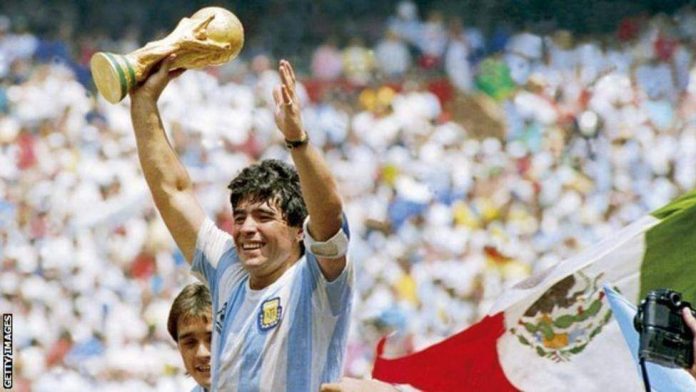

And in between it all came the moment that confirmed his status as something much more than merely a great footballer. How would things have transpired if Argentina had failed to beat England in the “Hand of God” match in the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, the “revenge” four years on of the defeat in the Falklands War?